How can one describe a female identity? It is typically tantamount to silhouettes and clothing: writers stain pages with descriptions of a woman’s dress and advertisements echo the sentiment of the prototypical female fixture. It is a never-ending designation of woman as object, a barrage of figurines that do not exist beyond their attire, let alone the kitchen. It was from the contours of these societal realities that we chose to focus our textile on the objectification and marginalization of women. In much the same way that Elaine Reichek’s Sampler eschews traditional female confines through subverting American textile-work’s historical monopoly of women, so too does our piece, Many Times I Returned, aim to undermine gendered stereotypes through a perversion of “feminine” tools. In creating this social garment, several textile-based methods were used.

The demure notions of womanhood associated with a fine white cotton glove are turned on their head in our work: a scarlet red warp runs through the hand-woven sleeve. It is not dainty, fragile or pure in its whiteness. Indeed, it is structured, almost industrial, laced with “millennial pink” — a nod to today’s #MeToo movement — and grounded in charcoal and ecru (colors used intentionally to draw attention to the integration of women of color and the heightened risks of sexual violence they face into the greater American feminist movement). Particularly emblematic is the scarlet red color of the warp and poufs woven into the textile, as it carries with it the memory of those who have died, and continue to die elsewhere in the world, for their struggle to bring female equality to the forefront of social change. A color of power, this bright red is further demonstrative of the relatively newfound strength derived from standing up in the face of gendered discrimination. Fringe made from tying off the ends of the warp hang from the wrist of the glove, signaling an homage to the key place in women’s rights history that the 1970s second-wave American feminism movement holds.

The weaving of the textile that constitutes the sleeve began with setting up the loom that we had constructed during class. The scarlet warp was woven to be about half of the maximum width that the loom could hold (so that upon completion of the textile, it would have the desired circumference to easily wrap around a forearm). Three types of “super bulky” yarn were then used as wefts: a semi-relaxed ecru-colored wool blend, a more tightly coiled heathered pink acrylic-wool blend, and a loosely woven charcoal acrylic-polyester blend. The first two rows were completed fully using a plain weave, and the following rows began to be offset in how much was completed of each for any particular yarn. This staggering of stitch is what gave way to the charcoal branching patterns and angled weaves. Further, although each yarn is classified as “super bulky,” the bulkiness still varied noticeably in weight and amount of coil. The ecru-colored yarn felt as if one were attempting to weave tufts of cotton—to be sure, this made it quite difficult to attain an even amount of “puff” amongst all said wool’s weaving. Distinctly, the pink acrylic-wool blend had a tendency to unravel itself when being manipulated through the tight warps (especially towards the end of the weaving, as much of the “give” that can be felt at the start of a weaving had been constrained from the amount that had already been woven). The charcoal-colored yarn also came with its own set of mishaps: a “homespun” blend, the loosely coiled yarn was held together with a single thread that had a propensity to pull apart with little tension, which resulted in a need to practice using the acrylic-polyester blend before incorporating it into the textile. Finally, cherry red “poufs” were formed by taking dense, dyed acrylic fibers and tying clumps together. They were then shaved down using scissors to achieve a more spherical shape. Since they had to be woven into the integrity of the textile, we could not just use pom-poms— we effectively had to find a way to make our own so that they could actually be a part of the weave and so that the sleeve would still rest flat upon the forearm when worn. In advance of the desired length of the textile being reached, the angled woven rows had to be justified. This process was arduous, as we had to be especially aware of the different widths and weights of the yarns (the thinnest yarn—the charcoal one— best kept the shape of the textile as it allowed for a tighter weave, but the pink and ecru yarns gave us the texture and patterns we wanted at the cost of widening the space between each warp). Once the weaving was completed, the respective ends were finished off, with the bottom end being turned into fringe for the aesthetic purposes of the final glove.

The simple gray mitten hidden under the fringe and holding the textile structure together was created by sewing two pieces of felt together. To further convey the progress of feminism in this current society, we wanted to use text to communicate our ideas. The embroidered letters were attached by using heat from an iron. Although there are many familiar words that are currently used to symbolize the feminist movement, we wanted to stay away from clichés. Emblazoned on the mitten’s face are the words “not there,” a reference to the progress needed to be made in America as well as to sexual assault and harassment. “Not there” could be a demand for “not there on my body”– a cry for stopping sexual assault. This association with hands parallels the hand that would be inside the mitten. On the backside of the mitten are the words “for now.” It sometimes seems hard to be optimistic about the progress that the feminist movement has made when there is so much to be done; however, these words represent hope for the future. There will be a time when we are “there” and societal equality is achieved. There is still a long struggle ahead, which is why the words are obfuscated by the red fringe on the palm of the mitten.

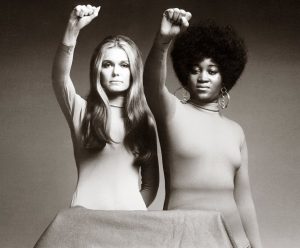

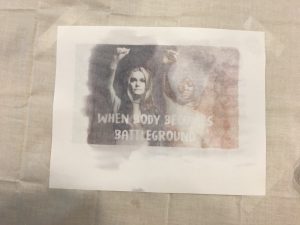

The two separate pieces — the woven cloth and the mitten — were hand sewn together using embroidery thread. To secure the elongated mitten on the wearer, we attached yarn on the sides of the woven cloth that are tied together when worn. As we wanted to give the glove shape when not being worn, we decided to use pieces of cotton cloth to fill out the hand-piece. Given that we were largely inspired by a seminal photo of Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman-Hughes, we transferred the ink of that photo in three different ways to the white cloth we intended to use. First, we pressed acetone and cotton balls to the back of a mirrored printed image so that, when color transferred, the image would be in accordance with the original. This first method is reflected in the cloth that has colors, as the acetone caused the ink to run. Next, we printed the mirrored image on wax paper and transferred it to another white cloth— this method allowed us to maintain the integrity of the grayscale ink. Finally, as the wax paper used brought streaking lines on the fabric’s image, we used baking parchment paper with the printed mirror image on it to transfer the ink to the cotton. This gave us our final result, as the image was true to the original and yet still maintained characteristics unique from the previous two methods. On the image, we had printed the words “when body becomes battleground” to further stress sentiments important to us in the social garment’s representative qualities. These words made the transferring process more detailed, as they required critical attention to be discernible without being overly-crisp (or even transferred on backwards).

This piece was inspired by the feminist movements throughout history, particularly the second-wave of feminism in 1970s America. As all females in this group, feminism and the #MeToo movement is incredibly important to all of us; these two movements are also closely tied together. We chose to go with one mitten, because we drew inspiration from a particular image of the feminist movement leaders, Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman-Hughes, where both women had one arm raised in power and in solidarity with one another (there were two images — one from 1971 and another from 2014 — since they later recreated the historic photo). In the first, the stern expression on their faces reflects the difficult times they were in, echoing the meaning we had for the words “not there.” In comparison, the image from 2014 showed both women with gentle smiles on their faces, paralleling the “for now” on the mitten. There has been progress made, and there is still so much more to go, but, they are hopeful for the future– just like we are.

Textiles continue to be important to the feminist movement. During the women’s march in 2017, women created the pussy hats social movement to raise awareness about social issues and to advance human rights dialogues. These hats made out of pink yarn are a new symbol of the current feminist movement. The current feminist movement in conjunction with the touch of “millennial pink” in our piece help speak to the words “for now.” We aren’t where we want to be yet as “not there” states but, we are on the rise and in the middle of huge change for women and their rights. #MeToo has begun such a powerful and inspiring stand for women and girls and has grown so much that people are finally starting to listen. Textiles are still so important to women’s clothing and women have been trying to change the idea that their clothing is the reason sexual abuse occurs. Not only are we changing perspectives of things with textiles, we are also working to change the perspective of textiles and their role in all these issues. Most people are used to seeing posters and signs in marches or protests but textiles can be so much more powerful. They are different than the usual sign and can speak volumes.