This project was a exercise in continuous readjustment. After finding out that the piece of wood we were each given was a little unconventional—or, at least, not a fully smooth and processed block of wood—I had to come up with a design that was feasible for the dimensions of the piece, while also not straining my technical abilities, as I had not completed the woodworking training. Originally, I figured that the shallow height of the wood could allow me to produce a simple circular bowl or dish (much akin to Peri’s final design!). So with this in mind, I asked my partner Taylor to use the band saw and power sander to cut my original piece into a circular shape—which she did effortlessly. However, I quickly found that this was by far the easiest part of the process, and that this would only be a small victory among a dozen blisters.

I set about hollowing out the inside of the circular block with the hand chisel in the maker space. This was an incredibly painstaking process: the tiny, dull chisel only scraped out a millimeter or two of wood shaving with every stroke. It also did not deliver the buttery satisfaction I had anticipated, as the way the original block was cut required me to chisel into the grain (essentially bisecting the grain) instead of with the grain. So instead of smooth and uniform shavings, I was only producing tiny, angry bite marks as I continued—each with jagged textures and different levels of depth. After four hours, I was left with a donut-shaped depression in the block, as seen  on the right (not pictured is the massive blister on my chiseling thumb). I knew that at this pace, it would be impossible to finish the bowl using this hand chisel; one of the workers at BEAM suggested that I relocate to the maker space in Hanes Art Center to use the dead blow hammer with a larger chisel to make the process move more quickly. Grateful, I took their advice and moved to Hanes.

on the right (not pictured is the massive blister on my chiseling thumb). I knew that at this pace, it would be impossible to finish the bowl using this hand chisel; one of the workers at BEAM suggested that I relocate to the maker space in Hanes Art Center to use the dead blow hammer with a larger chisel to make the process move more quickly. Grateful, I took their advice and moved to Hanes.

After securing the block in a metal vice grip, I attempted to use the hammer to drive the chisel into the center of the bowl the chip away the mound of wood still left there. Immediately, the block splintered, leaving a piece of the side of the bowl almost completely broken away. Already, it was clear that the hammer, in conjunction with the hardness of the wood, wouldn’t allow for chips to be taken out of the wood, and would only break the piece as a whole. So, still dead set on making a bowl, I went home for the night and thought of ways to soften the wood and to allow it to be more easily hollowed out.

I had the idea to soak the center of the bowl in water to create the pliability it needed in order to be removed. I thought I would localize the water by using a soaked paper towel and placing it in the middle of the mound, away from the rim of the bowl—but after checking on the progress of the soaking after about an hour, I realized, dismayed, that the water had seeped into the whole piece and had split apart the sides. This was a turning  point for me: at this point, I could not bear the thought of starting over with the hand chisel and hollowing out an entirely new bowl. The cracks were here to stay. So, I began to think of ways that I could incorporate the cracks into a final design, while making them as aesthetically uniform (and seemingly intentional) as possible.

point for me: at this point, I could not bear the thought of starting over with the hand chisel and hollowing out an entirely new bowl. The cracks were here to stay. So, I began to think of ways that I could incorporate the cracks into a final design, while making them as aesthetically uniform (and seemingly intentional) as possible.

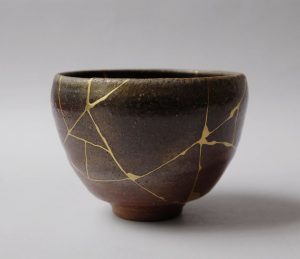

I remembered reading about kintsugi, a Japanese art of repairing broken ceramics by using lacquer mixed with powdered gold or silver. On one level, the result is visually stunning, but its philosophical underpinnings are fascinating as well: many believe that kintsugi derives from the Buddhist pra ctice of wabi-sabi, in which imperfections, faults, and failures are celebrated as beautiful and individualizing facets of human experience.In this light, kintsugi celebrates the failures of the artistic process, or the breakdown of the art object, by emphasizing its “faults,” rather than attempting to mask them.

ctice of wabi-sabi, in which imperfections, faults, and failures are celebrated as beautiful and individualizing facets of human experience.In this light, kintsugi celebrates the failures of the artistic process, or the breakdown of the art object, by emphasizing its “faults,” rather than attempting to mask them.

With all of the unexpected cracks that had appeared in my design, I realized that I could use the wood burner to similarly emphasize the cracks by giving them color, while also adding an aesthetic element to the piece. This was in fact the most enjoyable part of my process. With every crack that I touched with the wood burner, my bowl felt more and more salvaged—and better-looking—than it had moments before.

I also used the burner to add patterning to the previously stubborn mound in the center of the bowl: a flat tip, pressed onto the top of the mound, made it so only the areas that had not been chipped away were burned, leaving the depressed areas untouched (similar to wood engraving). The cracks radiating from the center unified all the burned areas, and my once disintegrating bowl now, for the first time, felt whole. It had been reborn as an ash tray.